A Dramatic Presentation

JEANNETTE SORRELL

Nicholas Phan, tenor – Evangelist

Jesse Blumberg, baritone – Jesus | Jeffrey Strauss, baritone – Pilate

Amanda Forsythe, soprano | Terry Wey, countertenor | Christian Immler, baritone

Video highlights from the dramatic production conceived and directed by Jeannette Sorrell, and presented by Apollo’s Fire in March 2016.

Filmed at Trinity Cathedral in Cleveland, Ohio. The production also toured nationally.

“A resplendent performance… The production belonged entirely to Ms. Sorrell, who devised the concept, which she called ‘a dramatic presentation’…. exquisite moments. The magnificent chorus [sang] to breathtaking effect…”

– New York Times

THE CONCEPT

Ms. Sorrell’s vision for the production sought to bring immediacy and clarity to Bach’s dramatic structure through several means. The “action” (storytelling) scenes take place on a specially lit platform in the center of the orchestra. All of the characters – Jesus, Pilate, Peter, etc. – perform their roles from memory, physically confronting each other on the platform. The “reflective” arias, in which Bach takes us outside of the story to contemplate what just transpired, are performed at the front of the stage, away from the drama platform. In the extended “mob” scene of the Trial Before Pilate and up through the climactic Condemnation of Jesus, half of the chorus is placed amongst the audience, shouting at Pilate from the aisles.

“Evokes deep spirituality while teeming with theatricality. Sorrell ensured that there was no lack of drama. A superlative performance.”

– Musical America

Videos are being added gradually, so please revisit this page. Preview/excerpt videos will be replaced with longer versions.

No. 1 CHORUS (preview-excerpt)

Herr, unser Herrscher, dessen Ruhm in allen Landen herrlich ist

Lord, thou our master, whose name in all lands is glorious…

No. 2-5

Jesus ging mit seinen Jüngern über den Bach Kidron

Jesus went with his disciples across the Kidron brook…

No. 16-18

Da ging Pilatus zu ihnen heraus und sprach…

Then Pontius Pilate went out unto them and said…

No. 20

Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken

Imagine that his blood-bespattered body…

No. 21-23

Und die Kriegsknechte flochten eine Kronen von Dornen

The soldiers made for him a crown of thorns…

No. 39-40

Ruht wohl, ihr heiligen Gebeine, die ich nun weiter nicht beweine

Rest well, beloved, sweetly sleeping, that I may cease from weeping…

A Passion with Passion

by Jeannette Sorrell

I. THE MUSIC

Bach Composes a Daring New Masterpiece

Last Saturday at noon, four wagons arrived here from Cöthen laden with the household effects belonging to the former Kapellmeister at the court of the Prince of that place who has now been invited to become Cantor in Leipzig. At two o’clock he himself arrived with his family and moved into the newly-renovated residence at the Thomasschule.

Thus, as the Leipzig press reported, did Bach and his family begin a new life in 1723. There are few musicians today who would give up a comfortable, well-paid post as resident musician to a Prince in exchange for a difficult and enormous church job. The fact that Johann Sebastian Bach decided in 1723 to trade his pleasant palace-musician post in Cöthen for the job of Kantor at Leipzig says much about the beliefs that shaped his life. The Leipzig position was a step downwards on the social scale, and it involved an almost insurmountable workload: composing, directing, and performing a new cantata every Sunday, assembling and directing an orchestra every week, teaching the boys’ choir at the Thommasschule, and even teaching non-musical subjects such as Latin. There can be only one reason why Bach took this position: he wanted to compose sacred music.

Bach was a profoundly religious man, famous for such comments in his keyboard teaching as, “the aim and final reason of the basso continuo, as of all music, should be none else but the glory of God and the refreshing of the mind.” In Leipzig, he immediately set to work, composing inspired cantatas that brought worlds of artistry to the contemplation of the traditional scriptures. His cantatas during Lent during that first year introduced new and dramatic elements, preparing his congregation to hear the groundbreaking masterpiece he was to unveil on Good Friday in 1724: his first major Passion-Oratorio, the St. John Passion.

The Passion-Oratorio as a genre was by no means invented by Bach, although his Passions are the most widely known today. Musical settings of the Christian Passion story were common already in the Middle Ages, and the Passion developed into its Lutheran form during the 17th century. Martin Luther was an extraordinarily passionate music-lover and was responsible for giving music a position of supreme importance in the Lutheran service. Luther expressed his feeling about music in his characteristically forthright way:

Music is a fair and lovely gift of God. Next to the Word of God, only music deserves to be extolled as the governess of the feeling of the human heart. This precious gift has been bestowed on men alone to remind them that they are created to praise and magnify the Lord. He who does not find this an inexpressible miracle of the Lord is truly a clod and is not worthy to be considered a man. (my italics)

In Bach’s time, Passions were composed by most of the leading musicians, including Telemann and Handel. And yet, their Passions have never made the impact on listeners that Bach’s have. Bach’s profound spiritual depth rings through his music in a way that transcends the compositions of his contemporaries.

The Passion form, as it had evolved by Bach’s time, was an oratorio intended as part of the Good Friday worship service. A sermon would have taken place between Parts 1 and 2. The music consists of recitatives narrating the Passion story verbatim from the Bible – in this case the Gospel of John – interspersed with arias and chorales set to contemporary (18th-century) religious poetry, reflecting on the Biblical passage just heard. Thus, sacred texts are interlaced with contemporary, more directly emotional material that speaks to the listeners in a universal way. (In fact, this concept has served as my own inspiration in creating two spiritual crossover programs for Apollo’s Fire: Sacrum Mysterium – A Celtic Christmas Vespers and Sephardic Journey – Wanderings of the Spanish Jews.)

In Bach’s Passions, the Biblical narration is performed by “the Evangelist” (i.e. St. John), while the dialogue spoken by Jesus, Peter, and Pilate is set as recitatives for solo singers stepping out of the chorus. Dialogue spoken by various groups of Chief Priests, crowds, etc., is sung by the chorus. A Bach Passion alternates between “action scenes” (where the Biblical story is relayed by the Evangelist-narrator and the characters), and contemplative arias and chorales (where we step outside of the story to reflect on the lessons to be learned as people of God). In our performance, I have tried to highlight the structure by placing the action scenes in the hands of true singing actors, who emerge in special spots on the stage to embody their roles.

It is not known for certain who compiled the 18th-century text that serves as the basis of the arias and chorales (as well as the opening chorus “Lord, our Master” and the closing chorus “Rest well”) in the St. John Passion, but it is quite possible that Bach did this himself. In any case, most of the text is drawn from the widely-used Passion text by Heinrich Brockes, which was also set by Handel and Telemann. It is noteworthy, however, that Bach made significant changes in the text to remove anti-Semitic passages. (The Brockes text essentially blames the Jews for Jesus’ crucifixion, whereas Bach’s St. John Passion text clearly places the guilt on each of us as sinners. This was also Luther’s view.) Since anti-Semitism was, unfortunately, a socially acceptable phenomenon in 18th-century Europe, I conclude that Bach made these changes not out of fear of controversy, but rather out of a desire to create a Passion on a higher spiritual level.

The St. John Passion is the work of a 39-year old man. It is filled with the extroverted emotions and daring of a great composer still in experimentation with this genre. This is a strikingly compressed telling of the Passion story; unlike the St. Matthew Passion, which luxuriates in an expansive and contemplative meditation on the Passion tale, St. John plunges us into a dramatic whirlwind of events from the very first recitative. This leads to a much more intense experience of the Crucifixion, in which the music serves as a counterpoint to the action. Particularly striking is the way in which the most tragic events are associated with triumphant music, such as the middle section of Es ist vollbracht (It is fulfilled), in which Christ is portrayed as a hero in battle. If the St. Matthew is the Passion of grandeur, St. John is the Passion with passion.

From the first swirling notes of the orchestral introduction, it is clear that Bach is taking us closer to opera than any of his church-music colleagues had dared to tread. The turbulent accompaniment paints a vivid picture of the events that are about to unfold. As with an operatic overture, we are drawn into the drama: the relentless, pulsating bass-line, like a beating heart, sets the stage for passion and terror. The surging motion in the violins evokes the chaos of the mob we will soon meet. And above it all, the long and anguished calls of the flutes and oboes lock in painful dissonances, like nails being driven into flesh.

This introduction builds up to the entrance of the chorus, which arrives with a surprising twist. Instead of the words of lamentation that the music has led us to expect – and that an 18th-century audience expected to hear in the Passions of the time – Bach gives us a song of praise to the universal reign of Christ: “O Lord, our Master, how excellent is thy name in all the earth!” Thus, Bach boldly breaks the baroque rule of Affekt, which normally decrees that each movement of a piece will have one particular emotional character. Instead, we have two Affekts simultaneously, as Christ’s glory and majesty are proclaimed, while Christ himself is looking down on the maelstrom of distressed humanity below. This stark duality runs through the Gospel of John: light and darkness, good and evil, truth and falsehood. Christ lifts up his cross in glory and draws all mankind to him – and yet he is also brought to the lowest of physical abasement, for the sake of humanity.

From there unfolds a drama of an intense and often mystical nature. I see the work as falling into seven Scenes (though they are not indicated by Bach) – two in the first half and five after intermission. Each scene propels the story forward and concludes with a reflective aria in which a singer steps out of the story to contemplate what we as the people of God can learn from this scene.

Bach’s use of the instruments at his disposal is colorful and often pungent. Plaintive oboes describe the shackles of our bondage to sin. Lighthearted flutes illustrate how Simon Peter (like all of us) follows Jesus with faithful footsteps. The full orchestra participates in the outcry of remorse at the end of Part 1, when Peter is filled with anguish for having denied his Savior. A lonely and haunting viola da gamba – a relatively rare guest in Bach’s orchestra – depicts Jesus’ battle with death in the famous Es ist vollbracht. And the other-worldly combination of flute and oboe da caccia accompanies the work’s one true lament, Zerflesse mein herz (“Dissolve in tears, my heart!”)

Our company of artists includes people of many faiths, as well as agnostics. And yet, we feel privileged to take this spiritual journey as we share Bach’s masterpiece with audiences around the world. We hope this recording rings with Bach’s message of hope and redemption for all people. – JS

II. THE TEXT

The Gospel of John – Text for a Mystical Passion

Das Newe Testament Deutzsch (Martin Luther, 1522) Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart

Bach chose the most “difficult” and mystical of the four Gospels – the Gospel According to St. John – for his first Passion. This is the Gospel that begins with the famous prologue, “In the beginning was the Word [Logos, cosmic reason], and the Word was with God, and the Word was God…. In Him was life, and the life was the light of men. And the light shines in the darkness and the darkness did not comprehend it.” (John 1:1, 4-5)

Chapter 21 of John’s Gospel states that this account is the eyewitness testimony of “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” The “beloved disciple” was traditionally thought to be the Apostle John – one of the Twelve Apostles. John’s personal and emotional responses to the unfolding events color Bach’s Passion throughout. The “beloved disciple” – that is, the Evangelist who is narrating our story – witnesses Jesus’ interrogation by the High Priest; speaks privately to the doorkeeper in order to get his comrade Peter into the palace; and is then shocked by Peter’s denial of Jesus, horrified by the behavior of the mob at the trial before the Roman governor (Pilatus or Pontius Pilate), and appalled when they chose to free a common murderer rather than freeing Jesus. John’s double role as narrator and character culminates when Jesus, in his final hour, gives his mother into the care of the “beloved disciple who was standing by.” In our production, this is the moment when the Evangelist breaks out of his narrator role to look directly at his beloved Teacher, dying on the cross – and we feel the profound love between them.

Though modern scholarship holds that the Gospel of John was written by several people, in Bach’s time it was still believed that the Apostle John was the author. Bach chose to end the final recitative of the St. John Passion with John’s statement about the purpose of his book: “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God and that believing, you may have life in his name.” Yes, John was an Evangelist.

The book of John arose in a Jewish Christian community in the process of breaking from the Jewish synagogue. It regularly describes Jesus’ opponents simply as “the Jews.” In later centuries, the book was unfortunately used to support anti-Semitic polemics. However, it is important to understand that the author(s) of the gospel regarded himself/themselves as Jews, championed Jesus and his followers as Jews, and probably wrote for a largely Jewish community. – JS

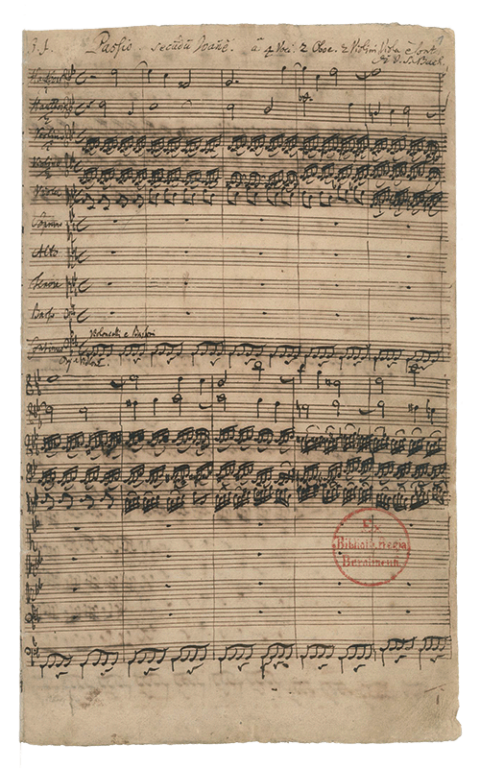

III. THE SOURCES

Bach performed the St. John Passion four times during his life – 1724, 1725, about 1730, and some time in the late 1740s. For each performance, he made changes to the score; thus, there is no definitive version. In the fourth performance, however, he returned to the original 1724 version, and since this seems to have been his final view of the work, this is the version we are performing. (The only exception is the “veil of the temple” recitative no. 33, for which we are using the more flamboyant version from 1725). The two scholarly editions of this work, the Bach Gesellschaft and the Neue Bach Ausgabe, differ in their interpretation of many ambivalences in the surviving performing parts, especially in the interpretation of slurs, which are notoriously unclear in Bach’s manuscripts. Rather than choosing one edition as sole authority over the other, I have considered both and have made artistic choices with the goals of musical coherence and faithfulness to Bach’s surviving manuscript material.

©2016 Jeannette Sorrell | Cleveland