Marlon Rucker

Senior Manager, PwC

heather

Notes on the Program – Mozart’s REQUIEM: A Tapestry

A Requiem for our Time

by Jeannette Sorrell

One of the blessings of being involved in the arts is that masterpieces from the past have a way of becoming relevant – sometimes painfully – in our own time.

In 1791, Mozart was composing his masterful Requiem against the backdrop of worldwide unrest and revolution – with struggles for democracy unfolding around him in France, Haiti, and the fledgling United States. The 35-year-old Mozart laid bare his soul in a work that remained unfinished. But that sense of incompleteness – the door left open, the words left hanging in the air – allows the work to be woven even more closely into the fabric of our own time.

I. Mozart’s Requiem: The Collision of Mysticism and Daily Life

And now I must go, just as it has become possible for me to live quietly. Now I must leave my art just as I had freed myself from the slavery of fashion, and won the privilege of following my own feelings and composing freely whatever my heart prompted! I must leave my poor children in the moment when I should have been able better to care for their welfare…. Did I not tell you that I was composing this “Requiem” for myself?

– Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, uttered on his deathbed (reported by Constanze Mozart)

Armand Mathey-Doret after Mihály Munkácsy (1844–1900)

I am fascinated by how the ordinary, banal events of daily life sometimes run on a parallel course with the mystical journey evolving in the souls of individuals. And, as if guided from above, the two courses eventually intersect. At such moments, something extraordinary is created. Mozart’s Requiem seems to be one of these creations.

On the path of the ordinary and banal events of daily life, we have the Count Franz von Walsegg, an eccentric but harmless country landowner, who liked to host musicales in his home, performing pieces he had secretly commissioned from respected composers. The twist: he liked to pass these pieces off as his own compositions. In the summer of 1791, the Count sent his representative to Mozart. The anonymous messenger appeared on Mozart’s doorstep, presented a commission for a Mass for the Dead, delivered half the fee, and warned that it would be a waste of time to attempt to learn the name of his employer.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

by Barbara Krafft (1764-1825)

I was initiated from earliest childhood in the mystical sanctuary of our religion… with all the vague but urgent feelings, one waits with a heart full of devotion for the divine service without really knowing what to expect; one rises lightened and uplifted without knowing what one has received; and one kneels under the touching strains of the Agnus Dei at the moment of the sacrament, with the music speaking in gentle joy from our hearts. True, this is lost in the hurly-burly of life. But in my case, when you take up the words you have heard a thousand times, for the purpose of setting them to music, everything comes back and you feel your soul moved again.

– Reported by Rochlitz in 1789

The two paths moved towards intersection in November 1791, when Mozart’s schedule lightened up after a highly successful run of The Magic Flute, which he conducted from the keyboard each night. Mozart sat down to begin the Requiem, and within a few weeks came thoughts of death – he believed he had been poisoned. Then came the illness that was to be his last. On 20 November he took to his bed and never left it again. The remaining sixteen days of his life were spent feverishly trying to finish the Requiem – his Requiem.

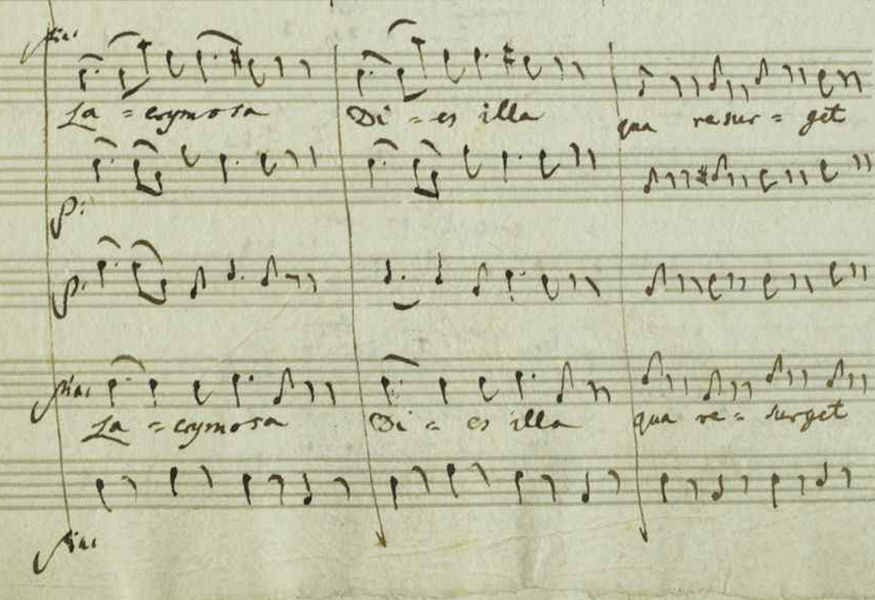

Mozart completed the Introit and sketched the other movements up through Hostias. Under his supervision, his students Freistadtler and Sussmayr wrote out the string doublings and the trumpet and timpani parts for the Kyrie. A third student, Eybler, orchestrated the Dies Irae, Tuba Mirum, Rex Tremendae, Recordare, and Confutatis, possibly under Mozart’s supervision. He wrote his contributions directly into the autograph manuscript. On 5 December Mozart composed the first eight bars of the Lacrimosa. And then he breathed his last. He was 36.

We have part of it, that is. A Requiem would normally have three more movements: the Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei. After Mozart’s death, his impoverished widow Constanze desperately tried to get the trio of students to finish the piece so that she could collect the commission. She gave the assignment first to Eybler (it is tempting to suggest that he was abler than the others), who felt that he could not continue past measure eight of the Lacrimosa. He returned the score to her.

Constanza then turned to Sussmayr, who was known not to be Mozart’s best student by any means – but he seems to have had more chutzpah than Eybler. He composed a completion for the Lacrimosa, as well as a Sanctus and Benedictus. We do not perform these, since I find them to be a detraction from Mozart’s work. In addition to the banality of the Sanctus, Sussmayr’s work suffers from some basic harmonic errors such as Neapolitan chords incorrectly resolved, hidden fifths, and other disturbing flaws.

Sussmayr cobbled together an Agnus Dei based on Mozart’s material. He claimed that Mozart instructed him to repeat the Kyrie fugue music at the end of the Agnus Dei. If this is true (which it might not be) it must have been a solution of desperation for Mozart – the only way to leave behind a performable Requiem. Having both finished and tarnished one of the greatest compositions in Western history, Sussmayr boldly forged Mozart’s signature on the manuscript, and off it went to the Count.

Since Mozart did leave us eight poignant bars of the Lacrimosa, several scholar-composers have taken up the challenge of completing that movement, following in Sussmayr’s steps but with the benefit of more hindsight. In the past, and on our CD album of the Requiem, we performed a lovely completion by René Schiffer, our principal cellist, whose compositions in various historical styles have won much praise in Europe and North America. This week, however, I am choosing to perform the Lacrimosa just as Mozart left it for us – unfinished and hanging in the air after just eight exquisite bars.

We in Apollo’s Fire are honored to be revisiting this piece for the third time, having performed it at our debut concert in 1992 (in a barn) and at our Tenth Anniversary Concert in 2002 (at Severance Hall). I am also overjoyed that seven of our longtime musicians who played in one or both of those concerts are still with us on stage this week – violinists Emi Tanabe and Marlisa del Cid Woody, violist Elizabeth Holzman Hagen, cellist René Schiffer, bassists Sue Yelanjian and Tracy Rowell, and flautist Kathie Stewart.

II. Weaving a Tapestry for our Time

How do you complete a concert program that consists mainly of a 38-minute incomplete masterpiece? As I pondered how to honor the legacy of Mozart’s unfinished Requiem, I thought about who Mozart was as a human being.

We know a lot from his letters. He was a humanist and an idealist; a member of the Masons, who in the 18th century represented the views of the Enlightenment. He was also a bold, controversial, and outspoken figure who cared very little for titles and hierarchy. He wrote an opera on a play that had been banned because it was disrespectful to the aristocracy. He knew he would surely get in trouble for this, but he did it anyway. Society in his time demanded that artists (who were considered servants) be utterly meek and subservient to their aristocratic bosses. Mozart failed at that in a rather spectacular way – and it cost him his career and his ability to earn a living.

I think he would not be meek. He never was.

In the present moment, as the world teeters on a precipice in many ways, I am hoping to honor Mozart’s legacy by creating a more inclusive context for his unfinished masterpiece. So, I am interweaving this European music with movements from sacred-inspired works by three of America’s leading Black composers – along with two traditional pieces from the wonderful repertoire of African American spirituals (a genre which I consider to be among America’s finest cultural contributions).

As we strive to honor the humanity within us all, I am thrilled to perform selections from Eric Gould’s powerful new composition, 1791: Requiem for the Ancestors, commissioned by Apollo’s Fire; from Damien Geter’s brilliant and acclaimed work, An African American Requiem (2019); and to share with our audience some of the work by internationally acclaimed composer Jessie Montgomery, as we perform two of her Five Freedom Songs (2020).

A Requiem Tapestry is intended to bring together neighbors from different walks of life in a spiritual journey. When our great bass-baritone Kevin Deas so powerfully evokes the presence of a Black preacher as he comes forward to sing Mozart’s Tuba Mirum, I know that the meaning of Mozart’s text will touch us all: “The trumpet will send its wondrous sound throughout earth’s sepulchres and gather all of us before the throne of God.” – All of us. We’re all in this journey together.

© Jeannette Sorrell, 2025 | Cleveland, Ohio

Chicago Board – Meehan, Michael

Michael J. Meehan

Cleveland Clinic, Retired General Counsel & Sec’y, Regional Hospital

Board – Olsen, Shay

Shay Olson

Retired bank operations, consulting and non-profit management specialist; former General Manager of Apollo’s Fire; former member of Apollo’s Singers

Board – Costante, Patricia

Patricia Costante

Managing Partner, Costante Alliance Management Consulting, LLC

Board – Powel, William

William A. Powel

Episcopal Diocese of Ohio, Canon to the Ordinary

Board – Cerveny, Kathleen

Kathleen Cerveny, Director Emeritus, ex officio

Cleveland Foundation, retired Program Director for Arts and Culture

Chicago Board – McPike, Marietta

Marietta McPike

Retired management executive, IBM; musician and piano teacher

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) is revered as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western music, having brought the style of the Classical period (1750-1820) to its culmination. He grew up in Austria as a renowned child prodigy, and composed over 800 works in his short life.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) is revered as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western music, having brought the style of the Classical period (1750-1820) to its culmination. He grew up in Austria as a renowned child prodigy, and composed over 800 works in his short life.

Growing up as a pianist and violinist, he composed his first piece at age five, and his first opera at twelve. As children, Mozart and his sister Maria Anna (known as Nannerl) traveled all over Europe, performing for royalty.

As a young adult, Mozart moved to Vienna and tried to earn a living as a pianist and composer. Though his concerts were very popular, he could not find an aristocratic patron who would provide him with a salary. Musicians were expected to behave like humble servants, but Mozart could not think of himself as a servant. Lacking a salary, his financial circumstances became increasingly dire. He died in poverty and in debt at the age of 35.

The Requiem, composed while he lay dying, is perhaps his most iconic and beloved work, but remains unfinished. Mozart instilled a sense of eternity in the work by borrowing “ancient” musical material, including themes from Handel’s The Ways of Zion do Mourn and the fugue “And with his stripes we are healed” from Handel’s Messiah. Over 20 composers and musicologists have developed alternative completions for the Requiem.

JESSIE MONTGOMERY

JESSIE MONTGOMERY is a GRAMMY® Award-winning composer, violinist, and educator whose work interweaves classical music with elements of vernacular music, improvisation, poetry, and social consciousness, making her an acute interpreter of 21st-century American sound and experience. Her profound works have been described as “turbulent, wildly colorful, and exploding with life,” (The Washington Post) and are performed regularly by leading orchestras, ensembles, and soloists around the world. In June 2024, Montgomery concluded a three-year appointment as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Mead Composer-in-Residence. She was named Performance Today’s 2025 Classical Woman of the Year.

JESSIE MONTGOMERY is a GRAMMY® Award-winning composer, violinist, and educator whose work interweaves classical music with elements of vernacular music, improvisation, poetry, and social consciousness, making her an acute interpreter of 21st-century American sound and experience. Her profound works have been described as “turbulent, wildly colorful, and exploding with life,” (The Washington Post) and are performed regularly by leading orchestras, ensembles, and soloists around the world. In June 2024, Montgomery concluded a three-year appointment as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Mead Composer-in-Residence. She was named Performance Today’s 2025 Classical Woman of the Year.

Montgomery’s music contains a breadth of musical depictions of the human experience—from statements on social justice themes, to the Black diasporic experience and its foundation in American music, to wistful adorations and playful spontaneity—reflective of her deeply rooted experience as a classical violinist and child of the radical New York City cultural scene of the 1980s and 90s. From choral-symphonic works such as I Have Something To Say (2019), to her more intimate solo instrumental works, she presents a fresh perspective on the contemporary concert music experience. In response to Montgomery’s GRAMMY®-winning work, Rounds (2021), San Francisco’s NPR station KQED stated: “this is what classical music needs in 2024.”

A founding member of PUBLIQuartet and a former member of the Catalyst Quartet, Montgomery is a frequent and highly engaged collaborator with performing musicians, composers, choreographers, playwrights, poets, and visual artists alike. Recent collaborations include a recording and touring project with Third Coast Percussion, including a newly-commissioned percussion quartet and an appearance with Montgomery as featured soloist in Lou Harrison’s Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra; a new work co-commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, Bravo! Vail Music Festival, and the Sphinx Organization; and an ongoing collaboration with choreographer Pam Tanowitz, which has led to several of her concert works being choreographed with major dance companies across the US, including the Nashville Ballet and the Miami Ballet. Montgomery’s interest in improvisation and collective music-making has led to the development of The Everything Band, which comprises eight composer-performers of varied stylistic backgrounds, including her long-time collaborator, bassist Eleonore Oppenheim, with whom she created the genre-bending improv duo, big dog little dog. Montgomery is also a founding member of the Blacknificent 7, a composer collective focused on presenting and supporting the works of Black composers through concert curation, scholarship, and mentorship.

At the heart of Montgomery’s work is a deep sense of community enrichment and a desire to create opportunities for young artists. During her tenure at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, she launched the Young Composers Initiative, which supports high school-aged youth in creating and presenting their works, including regular tutorials, reading sessions, and public performances. Her curatorial work engages a diverse community of concertgoers and aims to highlight the works of underrepresented composers in an effort to broaden audience experiences in classical music spaces.

Montgomery’s growing body of work includes solo, chamber, vocal, and orchestral works, as well as an opera in development with Lincoln Center Theater and The Metropolitan Opera, which explores family histories and the impact of her mother, playwright and actress Robbie McCauley, on the American historical narrative. Montgomery’s music has been heard on global stages across the US, Canada, Central America, Europe, and Asia, from the Hong Kong Cultural Center to the BBC Proms, Elbphilharmonie, Hollywood Bowl, and Carnegie Hall. Recent highlights include The Song of Nzingha (2024), part of soprano Karen Slack’s evening-length recital African Queens alongside other composers from the Blacknificent 7; Procession (2024), a percussion concerto written for Cynthia Yeh, Principal Percussionist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Space (2023), commissioned and performed by violinist Joshua Bell as part of his Elements project; Five Freedom Songs (2021), a song cycle conceived with and written for soprano Julia Bullock for the Sun Valley, Grand Teton, and Virginia Arts Music Festivals and San Francisco, Kansas City, Boston, and New Haven Symphony Orchestras; and I was waiting for the echo of a better day, a site-specific collaboration with Bard SummerScape and Pam Tanowitz Dance (2021).

Montgomery has been recognized with many prestigious awards and fellowships, including the Civitella Ranieri Fellowship, the Sphinx Medal of Excellence, the Leonard Bernstein Award from the ASCAP Foundation, and Musical America’s 2023 Composer of the Year. Since 1999, she has been affiliated with the Sphinx Organization in a variety of roles, including Composer-in-Residence for the Sphinx Virtuosi, its professional touring ensemble. Montgomery holds degrees from The Juilliard School and New York University and is currently a doctoral candidate in music composition at Princeton University. She serves on the Composition and Music Technology faculty at Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music.

ERIC GOULD

While his three CD’s have met with good success, and have enabled him to make a mark on the national jazz scene, these are but one aspect of a multi-dimensional career for pianist, composer, and arranger ERIC GOULD. As a bandleader, musician, producer, and educator, he has distinguished himself through his work and compiled a resume that allows him to move between various genres of music and areas of focus.

While his three CD’s have met with good success, and have enabled him to make a mark on the national jazz scene, these are but one aspect of a multi-dimensional career for pianist, composer, and arranger ERIC GOULD. As a bandleader, musician, producer, and educator, he has distinguished himself through his work and compiled a resume that allows him to move between various genres of music and areas of focus.

He has performed and recorded in collaboration with world-reknowned instrumentalists such as Ron Carter, Jimmy Heath, James Newton, Bobby Watson, Antonio Hart, Winard Harper, Cindy Blackman, Vanessa Rubin, Cecil Bridgewater, Talib Kibwe (T.K. Blue), Don Braden, Robin Eubanks, and Leon Lee Dorsey in addition to leading his own trio in performances from the Midwest to the East Coast. Gould has been a guest soloist with the Canton Symphony Orchestra and the Cleveland Philharmonic Orchestra. His debut CD, “On the Real” rose to number 11 on the national jazz radio charts in the first quarter of 1999. His second CD, “Miles Away… Wayne in Heavy” rose to number 10 on the national charts and to number 45 (out of over 2500 releases) for the year 2000. His third CD, “Who Sez?” has sold well from coast to coast.

Gould has composed music for various other ensembles as well. “Diaspora of the Drum,” his 30-minute work for chamber orchestra, jazz ensemble, and tap dancer was premiered in April, 2008 by Savion Glover with the GRAMMY®-Award winning Cleveland Chamber Symphony at Playhouse Square. “Bohemia After Dark,” his concert of arrangements of the music of Oscar Pettiford featuring legendary Ron Carter along with an all-star octet premiered at Tribeca Performing Arts Center in Manhattan in 2006. An orchestral arrangement of the concert was premiered at the Berklee College of Music in 2010. The Canton Symphony Commissioned his work for orchestra entitled “An American City” through the National Endowment for the Arts on the occasion of the bicentennial of Canton, Ohio in 2005. The Cleveland Chamber Symphony premiered his piece “Midnight Excursion” in 2003. In 1996 his piece for string quartet entitled “He Speaks in Shadows” was performed by the critically acclaimed Cavani String Quartet at Merkin Concert Hall in New York, at the Chamber Music America Festival in New York, and at the Britt Music Festival. His arrangement of the same piece for jazz quintet and orchestra was commissioned by the Canton Symphony Orchestra for a performance that took place in March, 2001. His piano quintet “The Fire Within” was premiered in 2014 at UNC Wilmington by the Cavani String Quartet. He was awarded a Meet the Composer Grant from Arts Midwest in 1994, and was selected as a member of their touring roster in 1985. He has also been a recipient of an Ohio Arts Council Individual Artists Fellowship for Composition.

As an educator, Gould is currently a Professor of Piano at Berklee. He served as Chair of the Jazz Composition Department at Berklee from 2012 to 2018. He served as Director of the Department of Music for the Cleveland Music School Settlement, one of the nation’s oldest and largest community music schools from 2007 to 2012, and was on the faculty at Cleveland State University from 2003 to 2008. He has also conducted numerous workshops, residencies, and classes, in addition to private instruction, festival organization, and arts management consultation. In his roles as Executive Director and Managing Consultant of the Excellence in Music Initiative in Cleveland, Ohio Gould played a substantial role in the development of the preparatory music program at Cuyahoga Community College.

His television credits include the 1984 PBS series entitled “North Coast Jazz,” which featured his duo “Umoja,” and a 2000 BET series entitled JazzEd TV that featured his Tri-C JazzFest concert with Cecil Bridgewater. He is the co-producer and host of an educational television show for the Smithsonian Institution entitled “Duke Ellington: Beyond Category” that aired in November, 1999 to over 4 million viewers at schools across the country.

In 2000, Gould served as a consultant for the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz National Curriculum Project. Gould has served as an advisory panelist for the National Jazz Service Organization, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Cleveland Music School Settlement, the Society for Public Access Computing (in the early days of the internet), and the Cleveland Arts Initiative Task Force. He served as Co-Chair of the Jazz/Special Projects grants panel for the National Endowment of the Arts in 1994 and as an individual artists grants panelist for the Arts Commission of Greater Toledo in 1986 and 1987. He holds a Master of Music degree in Composition from Cleveland State University, where he studied with Edwin London, Rudolph Bubalo, P.Q. Phan, and Andrew Rindfleisch.

Eric Gould currently resides in Brookline, MA, where he is active in composing, performing, teaching, recording, production, and arts management consultation. He is listed in the 2007 edition of “Who’s Who in America.”

DAMIEN GETER

DAMIEN GETER is an acclaimed American composer whose rapidly growing body of work includes chamber, vocal, orchestral, and full operatic works. He is also a celebrated bass-baritone – “amazing to listen to. Possessed of a rolling, resonant voice even at the lowest register” (Northwest Reverb) – whose varied credits include performances from the operatic stage to the television screen. Geter is Richmond Symphony’s Composer-in-Residence through 2026, and Composer-in-Residence for Fall 2025 at both Indiana State University’s Contemporary Music Festival and Ear Taxi Festival. He serves as Music Director for Portland Opera.

DAMIEN GETER is an acclaimed American composer whose rapidly growing body of work includes chamber, vocal, orchestral, and full operatic works. He is also a celebrated bass-baritone – “amazing to listen to. Possessed of a rolling, resonant voice even at the lowest register” (Northwest Reverb) – whose varied credits include performances from the operatic stage to the television screen. Geter is Richmond Symphony’s Composer-in-Residence through 2026, and Composer-in-Residence for Fall 2025 at both Indiana State University’s Contemporary Music Festival and Ear Taxi Festival. He serves as Music Director for Portland Opera.

Praised by The New Yorker for writing “beautifully for voices and elegantly for orchestra,” his “emotionally driven” (Opera) compositions are widely hailed for their “skillful vocal writing” (Wall Street Journal). In the 2025-2026 season, Geter’s brand new opera, Delta King’s Blues, with a libretto by Jarrod Lee, will be premiered by IN Series in Washington, DC, and Baltimore. The first full opera commissioned by IN Series, it celebrates the legacy of legendary guitarist Robert Johnson with a “blues opera” that tells the Faustian story of the bargain he struck with the devil: selling his immortal soul to learn the language of the blues. Geter’s song Amanirenas, commissioned by soprano Karen Slack for her African Queens art song program, continues to tour nationally at the Portland and Piedmont Operas, as well as the Naples Philharmonic in its orchestral premiere. His song cycle COTTON will be performed by Justin Austin, J’Nai Bridges, and Laura Ward at La Jolla Music Society. Additionally, Richmond Symphony premieres his Loving v. Virginia Suite, the Chicago Philharmonic and Richmond Symphony present An African American Requiem, Ear Taxi Festival presents I Said What I Said, VocalEssence presents The Justice Symphony, and Fresno Philharmonic performs Sinfonia Americana.

As a conductor, Geter leads Portland Opera in Verdi’s Requiem, joins Symphony New Hampshire to lead their Holiday Pops concert, and conducts Redlands Symphony in works by Britten, Copeland, and Teresa Carreño.

Last season marked the world premiere of Geter’s critically acclaimed Loving v. Virginia, featuring a libretto by Jessica Murphy Moo, which concluded Virginia Opera’s 50th anniversary season. Based on the true story of Mildred and Richard Loving, the opera – hailed as “nothing short of a masterpiece” by Operawire and “one of the most successful new operas of the decade” by Washington Classical Review – was co-commissioned by Virginia Opera and Richmond Symphony, co-produced by Virginia Opera and Minnesota Opera. His commissioned song, Gentle lady, do not sing, was included on the Choral Scholars University College Dublin’s album, Music by James Joyce, Volume I (September 2024, Signum Classics). He conducted performances of Paul Moravec’s opera The Shining, based on Stephen King’s iconic novel, at Portland Opera, and Carmel Symphony Orchestra’s Opening Night Gala, America the Beautiful concert.

In the 2023-24 season, Des Moines Metro Opera presented the full-length world premiere of Geter’s opera, American Apollo, to critical acclaim. Opera Now proclaimed Geter’s orchestrations created “a kaleidoscopic ‘American Impressionism’, with borrowings from other genres of the time, creating a diverse palate to accommodate the vivid characters,” and Opera Today stated the composer’s “sound palette and approach is very much his own distinct amalgamated voice.”

Called “superb” by The News Tribune, DC Theater Arts praises his “commanding presence and voice full of bass-baritone gravitas”. Recent season highlights include: his Metropolitan Opera debut in the GRAMMY® award-winning production of Porgy and Bess as the Undertaker; portraying abolitionist and historian William Still to great critical acclaim in Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Paul Moravec’s oratorio Sanctuary Road with Virginia Opera and Oakland Symphony; the title role of Quamino in the world premiere of Errollyn Wallen’s Quamino’s Map with Chicago Opera Theatre; as Angelotti in Tosca with the Portland and Eugene Operas; as Archibald Craven in The Secret Garden with Hawaii Opera Theatre; as Sam in Reno Symphony’s Voices of a Nation: Trouble in Tahiti; as the bass soloist in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Richmond Symphony and Fresno Philharmonic; Handel’s Messiah with North Carolina Symphony; joining Auburn Symphony Orchestra in Ralph Vaughan Williams’ A Sea Symphony; performing with Rembrandt Chamber Musicians in The Wayfarer’s Melodies: A Musical Journey, singing the John Ireland Songs of a Wayfarer cycle.

Additional operatic engagements have included portrayals of the Four Villains in Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann with Pacific Northwest Opera, and Colline in La bohème with the Tacoma and Vashon Operas. He has sung the Undertaker in Porgy and Bess and the Colonel in Zach Redler’s chamber opera The Falling and the Rising at Seattle Opera. A frequent favorite with Portland Opera, he has appeared as Dr. Grenville in La traviata, Alcindoro in La bohème, the Bass Slave in David Lang’s The Difficulty of Crossing a Field, as well as a soloist for Little Match Girl Passion, also by Lang. A highly sought-after recitalist and singer on the concert stage, Geter’s repertoire includes Mendelssohn’s Elijah; Beethoven’s 9th Symphony; the Brahms, Verdi, Fauré, and Mozart Requiems; Mozart’s Mass in C; Bach’s Cantata No. 3; Vaughn Williams’ Dona Nobis Pacem; and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8.

On television, Geter made his TV debut as John Sacks on NBC’s Grimm and was seen in Netflix’s Trinkets. Musical theater credits include Kevin Rosario in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights and Pontius Pilate in Jesus Christ Superstar.

Geter has been recognized by the Library of Virginia with its honorary Patron of Letters degree, was honored at the 2025 Strong Men & Women in Virginia History awards presented by Dominion Energy and the Library of Virginia, and was selected as a 2025 BRAVO! honoree by the Chesterfield Education Foundation.

He is an alumnus of the Austrian American Mozart Festival and the Aspen Opera Center, and was a semifinalist for the Irma Cooper Vocal Competition. He toured with the prestigious American Spiritual Ensemble, a group that helps promote preserving the American art form of the spiritual.

Damien Geter hosts the podcast ARTillery and is the owner of DG Music, Sans Fear Publishing. Music in Context: An Examination of Western European Music Through a Sociopolitical Lens, the book he co-authored, is available on Amazon or directly from the publisher, Kendall Hunt.

Chicago Board – Walker, David

David Walker, ex officio

Managing Director, Apollo’s Fire

Chicago Board – Sorrell, Jeannette

Jeannette Sorrell, ex officio

Artistic Director

Chicago Board – Bittenbender, Chuck

Chuck Bittenbender

President of the Board, Apollo’s Fire – Cleveland

Chicago Board – Sheinin, James

James C. Sheinin, M.D.

Retired physician, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Chicago Board – Nelson, Florence

Florence Nelson

Retired professional musician, President of Chicago Flute Club, former International Secretary-Treasurer of the American Federation of Musicians

Chicago Board – Davis, Blondean

Blondean Davis, Ed.D.

Superintendent, Matteson School District 162; CEO, Southland College Prep High School

Chicago Board – Costante, Patricia

Patricia Costante

Managing Partner, Costante Alliance Management Consulting, LLC

Chicago Board – Champi, Stephanie

Stephanie Champi

Education Consultant

Chicago Board – Angell, Michael

Michael Angell

Founder, Pistocelli Services

Community Advisor – White-Gould, Dianna

Dianna White-Gould

Dike School of the Arts, head of choral and keyboard studies

Community Advisor – Montezume, Nathalia

Nathália Montezuma

Theologian

Community Advisor – Alonso, Rodrigo

Rodrigo Lara Alonso

Music Educator, Latin American & Caribbean community liaison

Musical Pathway Fellowship Advisor (Cleveland Institute of Music)

Board – Weber, Ed

Ed Weber, D.O.

The Imaging Center, retired Diagnostic Radiologist